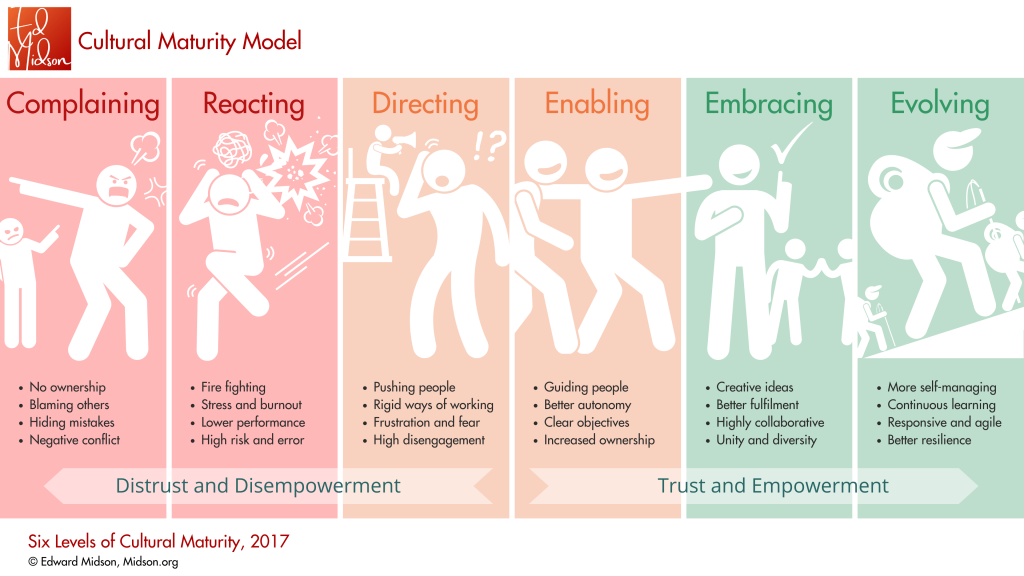

Level 1 – The Complaining Culture

In the launch edition of this series, I shared some of the thinking under the cultural maturity model as a whole. This time we’re looking at the least healthy level of cultural maturity; the complaining culture.

Let’s kick off with some reality checks. This behaviour set is at the hotter end of the red zone because of the dangerous by-products and results it can create. In a world where finally mental health is being taken seriously by many more organisations, I feel it is imperative that we draw out the similarities and almost comorbid characteristics that can begin to manifest in people working within these environments. For example, it is well documented that the emotional capital of an organisation affects every aspect of a business. How people feel at work impacts employee lifecycle, effectiveness and engagement. It can be tempting to believe this is an issue best served through resilience building, but I urge organisations to look more at the systemic and cultural factors contributing to low subjective and emotional wellbeing.

As if this was not impetus enough for leaders to take positive action, the health of the organisation itself is at a high risk of failure when operating from this position. Where the complaining culture takes hold, the lack of open communication and trust create blind spots and in turn reduce quality and compliance.

A nice reframe for this might be, imagine the potential that might as yet be untapped in your organisation by shifting to a more mature level.

The most important cultural indicator: Blame

The Complaining Culture has a cluster of specific behavioural indicators. While it is normal for people to complain, where this becomes a cultural concern is when some of the above behavioural indicators are also present. In this issue we will look at just one of the key challenges; blame.

Blame as a cultural trait

Where blame exists, so does fear. Where fear exists, honesty and accountability can be in short supply.

A “blame culture”, as it is commonly known, is where an organisation holds individuals or groups of people responsible for failures and mistakes. In these organisations people are often threatened with disciplinary action, asked to leave or forced to resign when something goes wrong.

As a consultant I have worked with several organisations who operate from this paradigm. It is common for government and public sector organisations or regulated environments and large firms with investors and shareholders to experience at least some aspects of a blame culture. This is because these kinds of organisations find it hard to exist in more mature ways in a world where they are scrutinised by their stakeholders, be they internal, commercial, regulatory or the public. The fact that the threat of being found in the wrong and held accountable for it exists is enough to cause a blame culture to become established. In fact, even the perception that there is one, is at the very heart of what purveys a complaining culture of disengagement.

So, what really is the impact of blame? The reason we blame is to deflect responsibility and defend ourselves against attack. If someone has to be held accountable (and accountable means punishment), when the chips are down many of us will seek to avoid or share blame.

Now, as a person you may hold a high value of honesty, you may have even fallen on a few swords in your career either to hold to that value or to shield others from blame. While this is in many ways admirable, it should not even be necessary. This is why we must extend some understanding to the many others who cannot remain so steadfast as you might in a blame culture, because being there is at times intoxicatingly frightening. So much hangs in the balance in these situations; “one wrong step and it’s all over” might feel an accurate internal narrative. To provide evidence that I’m not being slightly dramatic here, I would like to share the following example of how it can take just one person to create a blame culture within a senior team.

The day blame derailed me

A good few years ago, when I was still very new in the consulting sphere, I received one of the most powerful learnings of my career. I had been commissioned to design and run a leadership development programme for a group of very senior managers for a well-known organisation which shall remain nameless. Each of the executives were highly skilled and successful in their field. To this day, one of the most impressive groups of people I’ve ever worked with.

Yet, their Vice President was unhappy with them. In the initial meetings to discuss the development, the VP seemed very assured of their diagnosis. We asked to conduct some lightweight discovery activity before the pilot, but the VP insisted this would be a waste of time and money. They knew what they wanted. Reluctantly, I agreed to pursue their agenda, but I made it clear that the programme would be coaching led and as such our group sessions and one-to-one work would be steered by those attending the sessions.

It took longer than usual for people to really engage with the programme, with people appearing quite guarded in early sessions, and this was a sign that culturally there were issues with trust. However, about three months in, the attending executive team had begun to establish a relationship with myself and the delivery team. It was around this time we gained a much clearer picture as to the real issues underneath the situation. Here were a group of leaders being told to innovate and take risks, while feeling unable to do so due to fear of things not working right first time. We thought we’d cracked it!

At the next catch-up with our sponsor, we fed our findings back to the VP and agreed that we would hold a few trust development workshops.

At the first full day we had a great morning; understanding the nature of trust, how we each contribute to it and how we build an environment of trust. In the afternoon we turned our hand to the innovation challenges of the organisation and began to discuss how trust would be an essential ingredient. We asked each leader to share with the VP in a “safe space” what their greatest fear was about the future direction. When we went into the afternoon break everyone seemed lighter, happier and a few fed back that today had felt like “a huge breakthrough”.

This is until the final remarks from the VP that day. In their closing address to the leadership team the VP shared the following:

“I would like to thank Ed and the team for a really interesting day. I have been listening to what has been said, and I feel two things need to happen; One, in regard to your fears about the direction of the company, you need to get over it, and two, if you screw up, and it costs us money, you will get fired”.

I was floored. I simply could not believe the level of sabotage to the work we’d done and the complete lack of emotional intelligence. The entire group looked dismayed and shocked by the VPs words. Collectively, we tried to reason with the VP, but it was clear they were uninterested in revisiting the topic. It was also clear that while fear and blame were to reside there would be little we could do to shift the culture. In one swift move the VP had changed the situation. It dawned on us that our mission would have to change too; to support the Executives in coping with the cultural toxicity.

While we did this to the best of our ability, I have to say I don’t look back on this work with much pride. The suffering caused by one person championing a blame culture made delivering the programme highly remedial rather than developmental. While I feel the work we did was important, it gave me little joy. I was pleased to discover that shortly after our work finished, the VP left the organisation. I remember hoping that whoever replaced them would be more evolved in their leadership style. But one has to think; is this all that needed to change? Or are there more systemic issues that needed to be handled?

For me this is the epitome of low trust caused by a blame culture (i.e. “if I tell you I made a mistake you may fire me” or “if I admit I could have done that better, you’ll lose respect for me”). It is here that focus must be given if one is to shift a complaining culture being fuelled by blame and fear.

Here is the material point for us change agents

More often than not, if you can remove blame from your culture almost all of the other issues in this level of maturity can fall-away like dominos. Easily said than done for sure, but also really important to focus on. This leads me to say, the work on this area is never complete. Because trust is fundamental, we need to always be observing, preserving and nurturing it.

In the past, I’ve been highly tenacious in pursuing change inside this level of maturity. If, like I did back then, you think it is possible to lead an organisation towards innovation and sustainable growth that does not cost the mental health and wellbeing of all involved while blame exists in your organisation, let me unreservedly state for the record that you’re in for a very hard slog and likely huge disappointment.

Just like our work with the aforementioned client, it is not impossible to support people to cope effectively with such environments. But, knowing that the task is remedial rather than developmental means the house you’re building is set upon quicksand. It is in effect treating a symptom while ignoring the cause. And, having now tried this in at least three organisations, I can say from personal experience, blood, sweat and tears that the cost to you as the agent of change is likely to be substantial. Sure, you will learn a huge amount, it may even galvanise you for future situations, but there does come a point when enough is enough.

So, my top tips are: Know your limits. Know what needs to change. Be aware of the non-negotiables. Assess the political landscape and then buckle up and begin the work of changing it. But please also off-set your investment of passion and effort with a super-charged self-care strategy.

Next time

In the next article, we will build on some of the other characteristics of the complaining culture and its relationship to blame. We will explore how a lack of ownership and hiding of mistakes each threaten an organisation’s survival.